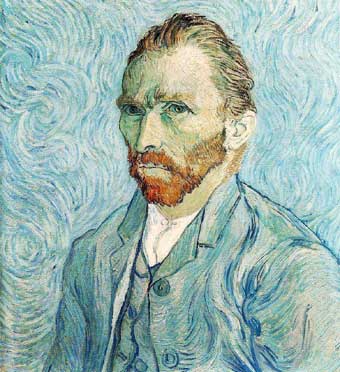

<< Changing colors..

<< Changing colors..@masterpiececreations

I'm homeless. If I think about it, the only thing that binds me to Japan is my citizenship and my physical attributes, and my undying appreciation for its food. Even my bloodline is groundless: half-Korean, quarter-Chinese, and quarter-Japanese. It makes me an Asian mutt.

Allegedly I don't even appear Japanese. I remember those days during grade school when I would commute via the train, and I would get curious - that's a euphemism - looks and glances from other Japanese commuters. All in all, my Japanese passport makes me a Japanese citizen. But, a thoroughly western education makes me something else that's not at all Japanese. Sure, I suppose I say that I 'return' to Tokyo, but it's not like I have an actual 'home' - in both the physical and metaphorical sense - to return to, let alone enough family members to ground my already-flimsy attachment. More often than not I feel like I'm more of a visitor than a returnee.

To be sure, many people who leave their hometowns for a while could feel like an alien upon their return. In a world where a few hundred dollars could buy you a return ticket across a couple continents, the reverse cultural shock and the consequent feeling of alienation is probably prevalent now more than ever. But I would argue that the key here is one's level of attachment to that first, so-called 'hometown'. The relationship, it seems, is entirely inverse: the stronger you recognised it as a 'hometown'/'home country' (prior to your departure and probably for a little while afterwards), the less trouble you had reconciling or coming to terms with your groundlessness. And vice versa.

I left Tokyo nearly seven years ago to go to Canada for university. When I finished my undergraduate degree, I moved back to Tokyo, and then a year later moved to England for grad school. Some would say that these decisions were quite the jump, even a courageous thing to do. Thank you - I'll take the compliment and saturate my ego in them for a little while. But really, it wasn't such a big deal at first, because I didn't leave anything all that valuable in Japan, other than my scattered family members. Friends were gone, the apartment in which we lived was gone, my belongings were all gone, my piano was gone. And with it went all the baggage that was attached to them. Leaving Tokyo was like finally cleaning up your room and purging it of all the unnecessary debris. I took all my valuables with me, mostly. Some pictures, but not very much. Some books. Clothes. CD's (it was just before the mp3 era). Money. And of course, that passport that, four years later, dragged me back to 'home', as some people would call it. Except, I don't, of course.

So when I finished university four years later, I felt frustrated by my Japanese passport dragging me back to a place I wasn't attached to. I was fully aware that there was, never was, and never will be in me, the same kind and level of patriotism or loyalty prevalent amongst my Canadian and American peers. In fact, that void was temporarily substituted by a sentimental attachment to Canada. This meant that this time around, I was leaving things that meant something to me. I felt like I was having to start life anew against my will. In four years I had grown some roots in Canada, and although I didn't ever quite feel like I'd adapt to the Canadian work ethic or smoke weed 24/7, Vancouver became the closest city to what an average person may call 'home'. And then, once again, I had to leave it.

So that is how my life goes on: in Japan, in England, and maybe back to Canada again at some point, or some other country, English-speaking or not. Who knows. It's exciting, you say? Sure, life can be exciting when things are changing. But such spontaneity only makes your life exciting when you have a home base to return to, not just to remind you of your roots, but so that you have a reference point. By reference point, I mean a family to return to, that same room whose door you can shut behind you, that same bed you can collapse onto and smell the same scent of clean laundry. When you have all that, a globetrotting life is full of great changes that awaken your senses to a swirling world of excitement. It allows you to appreciate all that is stable and all that is changing.

Recently, I've come to wonder whether this type of life was doing more harm than good. Only a select few would ever understand the structural issues inherent in a globetrotting life. After all, we third culture kids behave and think very differently from those who remained in one city or one country. More importantly, we are different from those exposed to one cultural environment for a prolonged period of time and by proxy, learned early on how to grow roots, and then uproot oneself without tearing the roots apart. For the latter, this life of a globetrotter may seem like a dream beyond a dream. All the travels, all the different people one gets to meet, all the world's wonders at one's feet to explore. But they have no idea what groundlessness does to people. You're always a fleeting kind of existence. Meeting people and saying goodbye. Creating something great and then having to leave it - even if it were a life's work. You almost have to build up a level of impermeable superficiality to deal with it, so that you can maintain somewhat of a core to what you think is who you are. You are at once required to adapt to your surroundings like a chameleon vanishing into its environs. But this oft-unquestioned act of instantaneous adaptation, the habit so carefully developed for survival purposes, also becomes a source of internal agony. Your values are always in question, your personality is always trying to adjust, and your life style is always altering.

Could you really imagine yourself in constant flux? I mean, your entire self!

So the question becomes, do I now opt for a life of geographic stability, and give up the rights and responsibilities of a globetrotter? Do I relinquish the liberties of a groundless wanderer, and place myself within certain bounds? I've never had that kind of life before, and the prospect of it is honestly scary.

Read more!